How the CBC and others make the military budget look tiny (when it's not)

Canada is actually one of the top military spenders in NATO

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has put tremendous pressure on NATO members to boost their military might through increased spending on troops, equipment, and missions.

Canada is no exception. At the meeting of NATO European and North American leaders this week, Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said, "We have always been committed to doing more on defence, and we will continue to do that."

To watch Canada’s news media, one might think that Canada is a low military spender within NATO. But take a look more closely, and the picture is different.

Canada is actually one of the top military spenders in NATO – ranking 6th highest amongst NATO’s 30 members.

Million US dollars 2021 (estimate)

1 United States $811,140

2 United Kingdom $72,765

3 Germany $64,785

4 France $58,729

5 Italy $29,763

6 Canada $26,523

7 Spain $14,875

8 Netherlands $14,378

9 Poland $13,369

10 Turkey $13,057

11 Norway $8,292

12 Greece $8,014

13 Belgium $6,503

14 Romania $5,785

15 Denmark $5,522

16 Czech Republic $4,013

17 Portugal $3,975

18 Hungary $2,907

19 Slovak Republic $2,043

20 Croatia $1,846

21 Lithuania $1,278

22 Bulgaria $1,253

23 Latvia $851

24 Estonia $787

25 Slovenia $760

26Luxembourg $474

27Albania $239

28 North Macedonia $219

29 Montenegro $97

Using NATO’s own figures, Canada is only behind the countries that have nuclear arsenals; U.S., U.K. and France, and two more countries that host American nuclear weapons; Germany and Italy.

So why does everyone say Canada is a small military spender?

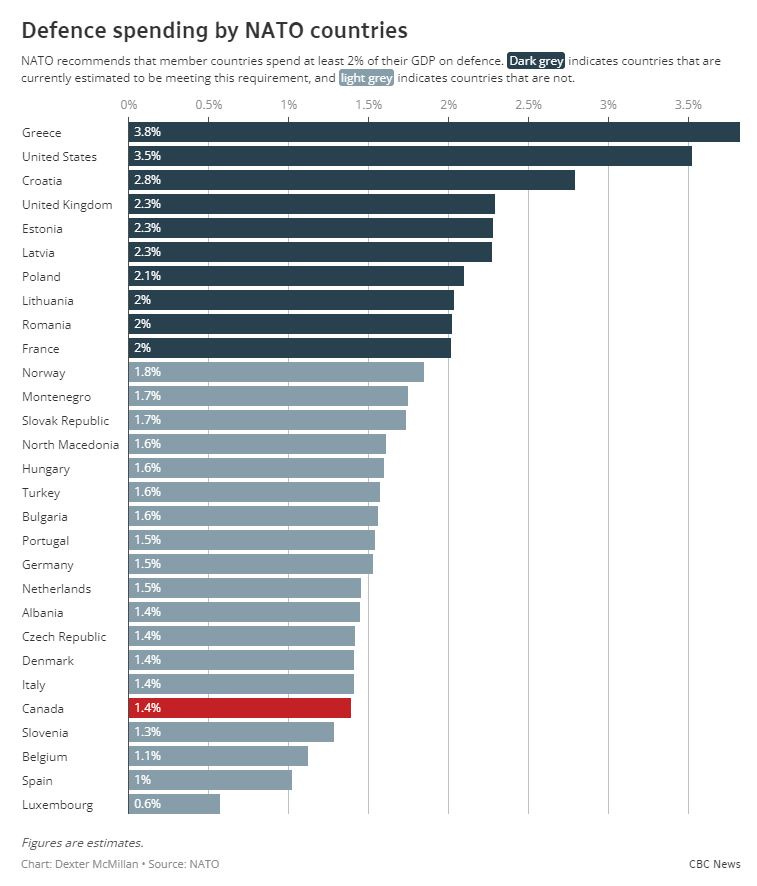

Back in 2018, NATO leaders agreed to a military spending target for each member country of 2% of GDP (GDP is the value of the entire economy).

Since then, NATO and American leaders have berated members for not reaching that 2% goal. U.S. President Trump once tweeted, “‘All NATO Nations must meet their 2% commitment, and that must ultimately go to 4%!”

The media joins in as well. Here is a recent article by CBC that makes Canada’s military spending seem absolutely puny. Look how far down the Canada appears on the CBCs list when comparing military spending as a percentage of GDP, when Canada's is actually 6th highest when compared using real dollars.

This week Defence Minister Anita Anand was grilled by the CBC about Canada’s “low” military spending until the Minister finally admitted she was taking a budget request to the Prime Minister and Cabinet for an increase to 2% GDP, and even higher – an expense that the Parliamentary Budget officer estimates to be $20-billion to $25-billion each year.

But the truth is that only a handful of countries actually hit that 2% goal - the nuclear powers (of course), and those small former Soviet countries on or near Russia’s border. In fact, only 10 of NATO’s 30 members spend 2% GDP or more on defence.

How does NATO compare military spending?

Each year NATO publishes a list of members’ defence spending, and it compares countries in three ways:

actual amounts (converted to U.S. dollars for comparison)

a percentage of GDP (the size of the economy)

per capita (the size of the population).

Each method has its role, but it’s a bit ironic that when describing our own military spending we compare percentage of GDP which makes it look smaller, but when we assess our “enemies’” military spending, we look at actual amounts. By the way, few people use the per capita comparison because it diminishes the appearance of military spending by countries with large populations, like China and India.

For instance, the U.S. raises alarm about another country’s rise in military spending (in amounts), such as China. But China’s economy has been growing at nearly 10% annually at times, so as a percentage of GDP its military spending could be staying the same or even shrinking. It’s a double-standard.

The best way to compare military spending is actual amounts. That's because real dollars measure how much fire-power a country can deploy - the real threat (or defence, depending upon where you stand).

What does the UN say about military spending?

The United Nations' founding document, the Charter, makes its views on military spending very clear in Article 26:

In order to promote the establishment and maintenance of international peace and security with the least diversion for armaments of the world's human and economic resources, the Security Council shall be responsible for formulating, with the assistance of the Military Staff Committee referred to in Article 47, plans to be submitted to the Members of the United Nations for the establishment of a system for the regulation of armaments. (emphasis added)

As the group Reaching Critical Will says, "Article 26 directly challenges and addresses militarism—the concept that international relations and national security can only be determined through the threat of military force, as well as continuous preparation and readiness for armed conflict. Article 26 demands disarmament and reduced military expenditures as a precondition for increased security, development, and peace."